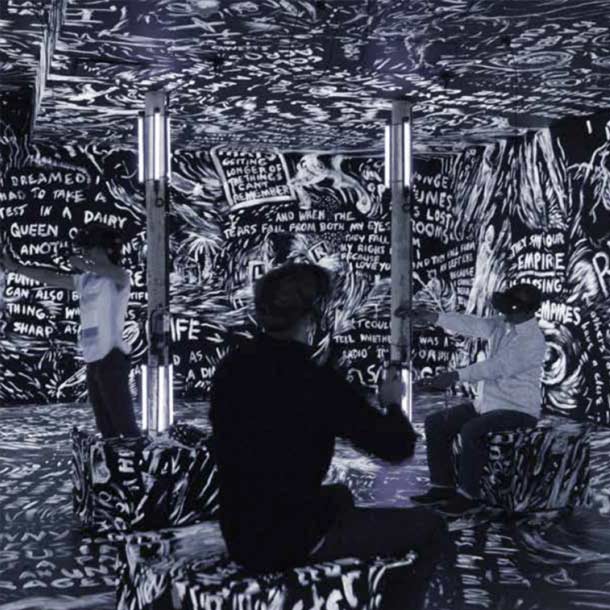

Chalkroom is a virtual reality work by Laurie Anderson and Hsin-Chien Huang in which the reader flies through an enormous structure made of words, drawings and stories. Once you enter you are free to roam and fly. Words sail through the air as emails. They fall into dust. They form and reform.

Chalkroom Installations

Mass MoCA

North Adams, MA, USA

May 2017 – Present

Louisiana Museum – Literature Festival

Humlebæk, Denmark

August 24-27 2017

74th Venice International Film Festival*

Venice, Italy

Sep 1-9, 2017

* Winner: Best VR Experience

Taipei Museum of Fine Arts

Taipei, Taiwan

November 17-???, 2017

“The best thing in Ms. Anderson’s show is “The Chalkroom,” a gallery covered in raw, white-on-black graffiti that expands into a haunting multichambered journey if you use its virtual reality component; her indelible voice on audio serves as the guide. It establishes Ms. Anderson as one of the artists VR was invented for.” – New York Times

Press Highlights

A Museum Where Giant Art Has Room to Breathe

The master plan for MASS MoCA in 1986 was a wildly ambitious dream: to simultaneously rehabilitate all 28 buildings of a shuttered 19th-century factory in this depressed Berkshire County town for the long-term display of monumental art installations.

Laurie Anderson: Filling Your Head With Living Stories

As a storyteller and performer, Ms. Anderson imagined a museum of her work might resemble a radio broadcasting station. That inspired the design of her glasswalled gallery, now to be her home away from her New York home. When she’s not in residency, you can listen to her recordings with headphones. Another gallery features her expressionistic charcoal drawings of her dog Lolabelle and visions of the Tibetan afterlife.

In a black-box gallery, white graffiti and drawings are scrawled across every plane of the room. There you can put on a virtual reality headset and lift off, tunneling through unfolding rooms with walls of her words. Drawings come to life and may turn into galaxies as Ms. Anderson’s voice fills your head with stories.

Virtual reality “does what I’ve always wanted to do as an artist from the time I’ve started, which is a kind of disembodiment,” Ms. Anderson said.

A second virtual experience puts you onto an airplane that peacefully disintegrates midair. As you drift through the heavens, reach for the floating Buddha or the copy of “Crime and Punishment” to trigger more storytelling. “It’s magic,” Ms. Anderson said. “You get to feel completely free.”

![]()

You are sitting, floating through the virtual clouds, when you hear that unmistakable voice coming through the headphones.

The glittering buildings. Paper being shredded on the floor.

It is Laurie Anderson, the artist most famous for her fluke 1981 hit “O Superman” but acclaimed for decades of creativity that have defied categorization. And this is “Aloft,” a new, virtual-reality piece at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art.

Over her long career, Anderson has made films, invented instruments, played the world’s greatest concert halls and also given outdoor shows for dogs. But she admits she’s shocked that her latest project has come together. It is a 10,000-square-foot studio in Mass MoCA’s newly renovated Building 6 and will serve as both an artistic incubator and a place fans can see her work for at least the next 15 years.

The Anderson project is part of a $65.4 million expansion at Mass MoCA, which has quietly become the country’s largest contemporary art campus. And talk of creating a space for the artist can be traced to a discussion at the museum nearly nine years ago when Mass MoCA Director Joseph C. Thompson turned and asked her a question: What would a museum of Laurie Anderson look like?

Laurie Anderson, renown for her use of technology in the arts, is creating a multifunctional exhibition space, audio archive and studio on permanent display at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art.

“She didn’t miss a beat,” Thompson said recently while walking through the museum. “She said, ‘It would be a radio station. And it would be a studio.’ Afterward, I said, ‘Would you be interested in trying to do “Radio Anderson?” ’ She said, ‘Yeah.’ ”

When the project finally came together several years later, Thompson called her back.

Her tone, she admits, was different.

“You’re kidding,” she told him, recounting the conversation recently. “I was literally shocked. I didn’t really think he was going to actually do this.”

But Thompson, who helped open Mass MoCA in 1999, has made it his specialty to pull off the unthinkable, whether an entire building dedicated to Sol LeWitt or the Wilco-curated Solid Sound music festival. The renovation of Building 6 is the latest, with dedicated installations featuring the works of Jenny Holzer, Robert Rauschenberg, Louise Bourgeois, Gunnar Schonbeck and James Turrell. Thompson imagines Anderson’s new space — which will include virtual-reality environments and a chalkboard room with floors, walls and a ceiling painted with cavelike messages — will offer a destination to which they can take a “Laurie Anderson pilgrimage.”

He’s excited about not just the technology but the floor-to-ceiling illustrations Anderson painted of her late dog, a rat terrier named Lolabelle.

“There are a lot of people who would have no clue that Laurie is a very fine draftsperson,” says Thompson. “She can draw, she can paint. She’s truly a multidimensional thinker and maker. A lot of people won’t give her the time of day. We hope this gives her not only the time of day but 15 years to show her work.”

Anderson says she’s excited about the project, but she tends to downplay the scope of the project or significance to her legacy. Her friends and collaborators say this is out of modesty. She particularly snickers at the word “pilgrimage.”

“That’s a word I find grating on me,” says Anderson. “For me, I don’t have that many things there at one time. I’m hoping to make the writing room or chalk room or whatever we’re calling it so people can go in a few different times. My dream is that they mostly feel this kind of feeling of being free and aloft.”

She also does not particularly like being referred to as a storyteller, though that is effectively what she does, whether through music, film or interactive objects. The Mass MoCA space will feature “The Handphone Table,” a 1978 piece that allows visitors to feel sounds by simply leaning elbows on its surface.

“Storyteller sounds like somebody in a library over-pronouncing words,” she says. “So I would say my medium are stories instead of I’m a storyteller.”

However she defines herself, Anderson’s work has stretched across decades, linking the experimental New York art scene of Yoko Ono and John Cage with Andy Kaufman, David Byrne and Philip Glass.

In 1992, she began dating Lou Reed, whom she would eventually marry, the union ending only in his death in 2013.

Reed is ever-present in Anderson’s life. She’s organizing his archives, has photos of him around her studio and incorporated his voice into her recent concerts with Glass.

“I had one long conversation that never stopped for 21 years, with one person,” she said recently during a break at Mass MoCA. “When that stops, you know it’s irreplaceable, but you begin to treasure your friends more, spend more time with them, and just kind of appreciate it more. I think I probably appreciate things more.”

She remains as active as ever. On a recent weekday, in her studio on Canal Street in New York, she tried to simultaneously conduct an interview while tracing out text for a display at Mass MoCA, edit a book she’s put together related to what she lost in Hurricane Sandy, and make a lunch reservation, for 10, to help celebrate a studio assistant’s birthday. She was also heading off to London for concerts with Glass.

On the wall next to her is a list of projects, current and future — “Lou recordings Yellow Pony, Lesbos? Landfall, Connie Converse” — that look as if they could keep the Museum of Modern Art’s curatorial department busy through the next presidential campaign. This, she says, is her norm. Or is it?

“I always try to do too much,” she says.

She pauses.

“Right now, it’s extreme, actually. Worse than usual. Tai chi and meditation are the things that make it possible for me not to flip out.”

Anderson is particularly excited about the VR project, a collaboration with Taiwanese artist Hsin-Chien Huang. Visitors can experience two environments with goggles and a headset. In the first, “Aloft,” the walls of an airplane slowly fall away, leaving the visitor floating in the clouds. An array of objects hover around — a crow, a flower, a conch, a cellphone — and each can be grabbed and held onto. That’s when Anderson’s voice pops up, telling a story or quoting literature until you toss the object out into the sky.

A second environment, “The Chalkroom,” features phrases and song lyrics painted in white on black walls.

“VR is usually about, it’s gaming stuff and it’s shooting stuff, it’s usually a very brittle and bright aesthetic,” she says. “We’ve kind of made something that is full of shadows and darkness. For me, it’s completely a dream come true. Because it’s about what I’ve tried to do in every other thing I’ve ever made. Music or sculpture or film. To be completely bodiless.”

This may be the first virtual-reality project she’s presented, but she has tried before. Michael Morris, who as co-director of London’s Artangel has worked with Anderson since her “O Superman” days, remembers trying to pull off a virtual-reality project that she was collaborating on with Peter Gabriel in the early ’90s. It simply couldn’t work because of the limitations of technology.

“For her, it’s attractive because it can help to tell the stories she wants to tell but it’s also participatory,” he says. “You can somehow create your own journey through the kinds of objects floating in the virtual reality and it doesn’t necessarily involve her as a performance. It’s a very intimate way of communicating when you’re not only wearing a headset and it’s you and her voice, which is a very extraordinary voice. I’ve never heard a voice like hers.”

In theory, the Mass MoCA project could have been a careercapper for Anderson, who turns 70 in June. But she resists that idea. She does not want it to be simply an archive, lined with shelves of old instruments or video monitors showing past performances. In that spirit, she says she will change the space regularly, a distinct difference between her galleries and those filled with the works of Turrell and LeWitt. She hasn’t even given her 10,000 square feet a name. For a time, Thompson called it “Radio Anderson.” She asked him to stop because she didn’t know what that meant. As it opens, it will simply be called “studio space.”

None of this surprises Roma Baran, her longtime musical collaborator.

She remembers, back in 1980, hearing Anderson perform a piece driven by a rhythmic, repeating voice loop and a series of conversations processed into electronic layers through a vocoder. She told Anderson she should put that piece out on a record. Anderson resisted until, finally, Baran somehow persuaded her. That was “O Superman.” It rose to No. 2 on the British charts.

“The idea that she would install something and kind of walk away and have people just dust it is not thinkable really,” she says.